Stop me if you’ve heard any of the following before:

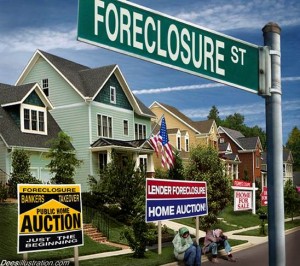

Exploding ARMs to subprime borrowers kicked off the nation’s housing and ensuing financial crisis.

Mortgages during the boom era were designed to fail, and everyone making the loans knew it.

Financial innovation ran amok in U.S. mortgage markets in the 2000s, driving unsafe lending.

Government policies, or lack of them, enabled overheated and unsafe lending.

The originate-to-distribute model enabled bad lending decisions, and securitization is solely to blame.

Investors buying mortgage-backed securities were fleeced by industry insiders, and never understood the risks of what they were buying.

But what if all of what we think we know about the financial crisis and housing meltdown isn’t true?

That’s the seemingly astonishing assertion from researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, in a paper published last week. That this paper, penned by three Federal Reserve Bank economists, hasn’t become a hot-burner discussion item thus far is perhaps even more astonishing.

Reading the paper – titled Why Did So Many People Make So Many Ex Post Bad Decisions? The Causes of the Foreclosure Crisis – in some ways felt like my own personal version of The Matrix, one of my favorite movies from the late 1990s. In the movie, lead character Neo is “unplugged” from what he thought was reality and presented with an alternate reality.

Fed economists Christopher Foote, Kristopher Gerardi, and Paul Willen apparently decided the time has come to try to unplug at least some people from a financial markets version of The Matrix: that is, common knowledge about the financial crisis and associated housing collapse. And their paper makes for gripping reading to anyone who has spent the majority of their professional life in the financial markets.

In various turns, the authors end up arguing that much of what we think we know about the financial crisis is, in fact, not actually rooted in fact at all.

For example, the authors find little evidence that payment shocks to subprime borrowers had anything to do with the lead-in to the housing meltdown during 2007. “The overwhelming majority of foreclosed borrowers—84 percent—were making the same payment at the time they first defaulted as when they originated their loans,” Foote et al write.

So much for so-called “exploding ARMs,” then?

Foote, Gerardi and Willen argue the problem wasn’t that loans were inherently built to fail: instead, they say, it’s that the lending market and consumers alike were ill-prepared to withstand a stunning drop in home prices.

Another bombshell in this paper takes aim at those who claim varying government policies in the 1990s and early 2000s enabled the crisis: the authors instead detail how the GI Bill of 1944 led to a world where by the late 1960s, the average down payment on a VA loan was around 2 percent at a time when FHA and VA loans were as dominant in the loan marketplace as they are today. Foote et al argue that government policy was remarkably stable towards housing during the 1990 to 2005 period, in contrast to prior periods, and contrary to popular narrative.

What, me worry?

Perhaps the most interesting discussion in the paper is saved for the middle, however, where the authors tackle what has become a legal minefield as of late: investors. Investors putting money into RMBS deals had plenty of information and knew exactly what the risks of their investment were, Foote et al argue — certainly a far cry from the investor-lawsuit headlines many in the financial press have been running with.

“Investors knowingly bought low-doc/no-doc loans,” according to the paper. “In fact, we now know that lenders provided loans to borrowers with damaged credit without documenting their incomes not because of any after-the-fact forensic investigation, but rather because lenders broadcasted this information to prospective investors.”

The authors go even further, saying that beyond having access to the information and having the tools necessary to model credit risk, investors also understood the risks inherent in their investments when they made them.

“[I]nvestors were able to predict with a fair degree of accuracy how mortgages and related securities would perform under various macroeconomic scenarios,” the authors argue. Whether they chose to perform the analysis – or more importantly, believe their analysis, as the authors argue – is another matter. Which begs the question: if investors knew what could happen if home prices dropped, why did they then still buy?

For Foote et al, it comes down to one very simple but powerful insight: during the boom, adverse home price scenarios that saw home prices drop 5% or more received very little weight, either from the buy-side or the sell-side.

In the home buying mania that pervaded the early 2000s, investors and home buyers alike believed home prices could only go in one direction: up. (We know how that story ended, of course.)

While the authors make a number of policy recommendations relative to preventing future instabliity in financial markets, perhaps the best of the paper’s suggestion is ultimately also the most obvious: inform home buyers that prices might, you know, actually go down.

“If we are going to invest in financial education, we need to teach everyone—from first-time homebuyers to Wall Street CEOs—that asset prices move in ways we do not yet understand,” Foote et al write. “Unfortunately, none of the new disclosure forms proposed by regulators includes the critical piece of information borrowers need to know: there is a chance that the house they are buying will soon be worth substantially less than the outstanding balance on the mortgage.”

Would that have stopped a soon-to-be overextended borrower in their tracks? Eh, probably not.

But in a Matrix-like world where financial reality increasingly isn’t always what we tend to think it is, a little jolt of reality might have helped at least some people find a way to unplug themselves from the bubble.

by Paul Jackson of HousingWire