by Daniel Pipes

Middle East Quarterly

Fall 2009

When Barack Obama announced in June 2009 about Israeli-Palestinian diplomacy, “I’m confident that if we stick with it, having started early, that we can make some serious progress this year,” he displayed a touching, if naïve optimism.

Indeed, his determination fits a well-established pattern of determination by politicians to “solve” the Arab-Israeli conflict; there were fourteen U.S. government initiatives just during the two George W. Bush administrations. Might this time be different? Will trying harder or being more clever end the conflict?

No, there is no chance whatever of this effort working.

Without looking at the specifics of the Obama approach — which are in themselves problematic — I shall argue three points: that past Israeli-Palestinian negotiations have failed; that their failure resulted from an Israeli illusion about avoiding war; and that Washington should urge Jerusalem to forego negotiations and return instead to its earlier and more successful policy of fighting for victory.

I. Reviewing the “Peace Process”

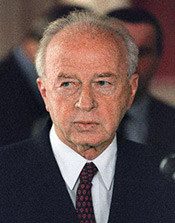

The two hands of September 1993, when Yitzhak Rabin and Yasir Arafat shook hands with President Clinton watching. |

It is embarrassing to recall the elation and expectations that accompanied the signing of the Oslo accords in September 1993 when Israel’s prime minister Yitzhak Rabin shook hands on the White House lawn with Yasir Arafat, the Palestinian leader. For some years afterward, “The Handshake” (as it was then capitalized) served as the symbol of brilliant diplomacy, whereby each side achieved what it most wanted: dignity and autonomy for the Palestinians, recognition and security for the Israelis.

President Bill Clinton hosted the ceremony and lauded the deal as a “great occasion of history.” Secretary of State Warren Christopher concluded that “the impossible is within our reach.” Yasir Arafat called the signing an “historic event, inaugurating a new epoch.” Israel’s foreign minister Shimon Peres said one could see in it “the outline of peace in the Middle East.”

The press displayed similar expectations. Anthony Lewis, a New York Times columnist, deemed the agreement “stunning” and “ingeniously built.” Time magazine made Arafat and Rabin two of its “men of the year” for 1993. To cap it off, Arafat, Rabin, and Peres jointly won the Nobel Peace Prize for 1994.

As the accords led to a deterioration of conditions for Palestinians and Israelis, rather than the expected improvement, these heady anticipations quickly dissipated.

When Palestinians still lived under Israeli control, pre-Oslo accords, they had benefited from the rule of law and a growing economy, independent of international welfare. They enjoyed functioning schools and hospitals; they traveled without checkpoints and had free access to Israeli territory. They even founded several universities. Terrorism declined as acceptance of Israel increased. Oslo then brought Palestinians not peace and prosperity, but tyranny, failed institutions, poverty, corruption, a death cult, suicide factories, and Islamist radicalization. Yasir Arafat had promised to build his new dominion into a Middle Eastern Singapore, but the reality he ruled became a nightmare of dependence, inhumanity, and loathing, more akin to Liberia or the Congo.

The two hands of October 2000, when a young Palestinian showed off his bloody hands after lynching two Israeli reservists. |

As for Israelis, they watched as Palestinian rage spiraled upward, inflicting unprecedented violence on them; the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs reports that more Israelis were killed by Palestinian terrorists in the five years after the Oslo accords than in the fifteen years preceding it. If the two hands in the Rabin-Arafat handshake symbolized Oslo’s early hopes, the two bloody hands of a young Palestinian male who had just lynched Israeli reservists in Ramallah in October 2000 represented its dismal end. In addition, Oslo did great damage to Israel’s standing internationally, resurrecting questions about the very existence of a sovereign Jewish state, especially on the Left, and spawning moral perversions such as the U.N. World Conference against Racism in Durban. From Israel’s perspective, the seven years of Oslo diplomacy, 1993-2000, largely undid forty-five years of success in warfare.

Palestinians and Israelis agree on little, but with a near universality they concur that the Oslo accords failed. What is called the “peace process” should rather be called the “war process.”

II. The False Hope of Finessing War

Why did things go so badly wrong? Where lay the flaws in so promising an agreement?

Yitzhak Rabin’s understanding that “One does not make peace with one’s friends. One makes peace with one’s enemy” led Arab-Israeli diplomacy fundamentally astray. |

Of a multiplicity of errors, the ultimate mistake lay in Yitzhak Rabin’s misunderstanding of how war ends, as revealed by his catch-phrase, “One does not make peace with one’s friends. One makes peace with one’s enemy.” The Israeli prime minister expected war to be concluded through goodwill, conciliation, mediation, flexibility, restraint, generosity, and compromise, topped off with signatures on official documents. In this spirit, his government and those of his three successors — Shimon Peres, Binyamin Netanyahu, Ehud Barak — initiated an array of concessions, hoping and expecting the Palestinians to reciprocate.

They did not. In fact, Israeli concessions inflamed Palestinian hostility. Palestinians interpreted Israeli efforts to “make peace” as signals of demoralization and weakness. “Painful concessions” reduced the Palestinian awe of Israel, made the Jewish state appear vulnerable, and incited irredentist dreams of annihilation. Each Oslo-negotiated gesture by Israel further exhilarated, radicalized, and mobilized the Palestinian body politic to war. The quiet hope of 1993 to eliminate Israel gained traction, becoming a deafening demand by 2000. Venomous speech and violent actions soared. Polls and votes in recent years suggest that a mere 20 percent of Palestinians accept the existence of a Jewish state.

Rabin’s mistake was simple and profound: One cannot “make peace with one’s enemy,” as he imagined. Rather, one makes peace with one’s former enemy. Peace nearly always requires one side in a conflict to be defeated and thus give up its goals.

Wars end not through goodwill but through victory. “Let your great object [in war] be victory” observed Sun Tzu, the ancient Chinese strategist. “War is an act of violence to compel the enemy to fulfill our will,” wrote his nineteenth-century Prussian successor, Karl von Clausewitz in 1832. Douglas MacArthur observed in 1951 that in “war, there is no substitute for victory.”

Technological advancement has not altered this insight. Fighting either continues or potentially can resume so long as both sides hope to achieve their war goals. Victory consists of imposing one’s will on the enemy, compelling him to give up his war ambitions. Wars typically end when one side gives up hope, when its will to fight has been crushed.

Defeat, one might think, usually follows on devastating battlefield losses, as was the case of the Axis in 1945. But that has rarely occurred during the past sixty years. Battlefield losses by the Arab states to Israel in 1948-82, by North Korea in 1953, by Saddam Hussein in 1991, and by Iraqi Sunnis in 2003 did not translate into despair and surrender. Morale and will matter more these days. Although they out-manned and out-gunned their foes, the French gave up in Algeria, the Americans in Vietnam, and the Soviets in Afghanistan. The Cold War ended, notably, with barely a fatality. Crushing the enemy’s will to fight, then, does not necessarily mean crushing the enemy.

Arabs and Israelis since 1948 have pursued static and opposite goals: Arabs fought to eliminate Israel; Israelis fought to win their neighbors’ acceptance. Details have varied over the decades with multiple ideologies, strategies, and leading actors, but the twin goals have remained in place and unbridgeable. If the conflict is to end, one side must lose and one side win. Either there will be no more Zionist state or it will be accepted by its neighbors. Those are the only two scenarios for ending the conflict. Anything else is unstable and a premise for further warfare.

The Arabs have pursued their war aims with patience, determination, and purpose; the exceptions to this pattern (e.g., the Egyptian and Jordanian peace treaties) have been operationally insignificant because they have not tamped hostility to Israel’s existence. In response, Israelis sustained a formidable record of strategic vision and tactical brilliance in the period 1948-93. Over time, however, as Israel developed into a wealthy country, its populace grew impatient with the humiliating, slow, boring, bitter, and expensive task of convincing Arabs to accept their political existence. By now, few in Israel still see victory as the goal; almost no major political figure on the scene today calls for victory in war. Uzi Landau, currently minister of national infrastructure, who argues that “when you’re in a war you want to win the war,” is the rare exception.

The Hard Work of Winning

In place of victory, Israelis developed an imaginative array of approaches to manage the conflict:

- Territorial compromise: Yitzhak Rabin (and the Oslo process).

- Develop the Palestinian economy: Shimon Peres (and the Oslo process).

- Unilateralism (build a wall, withdraw from Gaza): Ariel Sharon, Ehud Olmert, and the Kadima party.

- Lease the land under Israeli towns on the West Bank for 99 years: Amir Peretz and the Labor Party.

- Encourage the Palestinians to develop good government: Natan Sharansky (and George W. Bush).

- Territorial retreat: Israel’s Left.

- Exclude disloyal Palestinians from Israeli citizenship: Avigdor Lieberman.

- Offer Jordan as Palestine: elements of Israel’s Right.

- Expel Palestinians from lands controlled by Israel: Meir Kahane.

Contradictory in spirit and mutually exclusive as they are, these approaches all aim to finesse war rather than win it. Not one of them addresses the need to break the Palestinian will to fight. Just as the Oslo negotiations failed, I predict that so too will every Israeli scheme that avoids the hard work of winning.

Ehud Olmert speaking for the Israel Policy Forum in June 2005, where he announced that Israelis “are tired of fighting, we are tired of being courageous, we are tired of winning, we are tired of defeating our enemies.” |

Since 1993, in brief, the Arabs have sought victory while Israelis sought compromise. In this spirit, Israelis openly announced their fatigue with warfare. Shortly before becoming prime minister, Ehud Olmert said on behalf of his countrymen: “We are tired of fighting; we are tired of being courageous; we are tired of winning; we are tired of defeating our enemies.” After becoming prime minister, Olmert proclaimed: “Peace is achieved through concessions. We all know that.” Such defeatist statements prompted Yoram Hazony of the Shalem Center to characterize Israelis as “an exhausted people, confused and without direction.”

But who does not win, loses. To survive, Israelis eventually must return to their pre-1993 policy of establishing that Israel is strong, tough, and permanent. That is achieved through deterrence — the tedious task of convincing Palestinians and others that the Jewish state will endure and that dreams of elimination must fail.

This will not be easy or quick. Due to missteps during the Oslo years and after (especially the unilateral withdrawal from Gaza of 2005 and the Lebanon war of 2006), Palestinians perceive Israel as economically and militarily strong but morally and politically weak. In the pungent words of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, Israel is “weaker than a spider’s web.” Such scorn will likely require decades of hard work to reverse. Nor will it be pretty: Defeat in war typically entails that the loser experience deprivation, failure, and despair.

Israel does enjoy one piece of good fortune: It need only deter the Palestinians, not the whole Arab and Muslim populations. Moroccans, Iranians, Malaysians, and others take their cues from the Palestinians and with time will follow their lead. Israel’s ultimate enemy, the one whose will it needs to crush, is roughly the same demographic size as itself.

This process may be seen through a simple prism. Any development that encourages Palestinians to think they can eliminate Israel is negative, any that encourages them to give up that goal is positive.

The Palestinians’ defeat will be recognizable when, over a protracted period and with complete consistency, they prove that they have accepted Israel. This does not mean loving Zion, but it does mean permanently accepting it — overhauling the educational system to take out the demonization of Jews and Israel, telling the truth about Jewish ties to Jerusalem, and accepting normal commercial, cultural, and human relations with Israelis.

Palestinian démarches and letters to the editor are acceptable but violence is not. The quiet that follows must be consistent and enduring. Symbolically, one can conclude that Palestinians have accepted Israel and the war is over when Jews living in Hebron (on the West Bank) have no more need for security than Arabs living in Nazareth (in Israel).

III. U.S. Policy

Like all outsiders to the conflict, Americans face a stark choice: Endorse the Palestinian goal of eliminating Israel or endorse Israel’s goal of winning its neighbors’ acceptance.

To state the choice makes clear that there is no choice — the first is barbaric, the second civilized. No decent person can endorse the Palestinians’ genocidal goal of eliminating their neighbor. Following every president since Harry S Truman, and every congressional resolution and vote since then, the U.S. government must stand with Israel in its drive to win acceptance.

Not only is this an obvious moral choice, but Israel’s win, ironically, would be the best thing that ever happened to the Palestinians. Compelling them finally to give up on their irredentist dream would liberate them to focus on their own polity, economy, society, and culture. Palestinians need to experience the crucible of defeat to become a normal people — one whose parents stop celebrating their children becoming suicide terrorists, whose obsession with Zionist rejectionism collapses. There is no shortcut.

This analysis implies a radically different approach for the U.S. government from the current one. On the negative side, it puts Palestinians on notice that benefits will flow to them only after they prove their acceptance of Israel. Until then — no diplomacy, no discussion of final status, no recognition as a state, and certainly no financial aid or weapons.

On the positive side, the U. S. administration should work with Israel, the Arab states, and others to induce the Palestinians to accept Israel’s existence by convincing them that they have lost. This means impressing on the Israeli government the need not just to defend itself but to take steps to demonstrate to Palestinians the hopelessness of their cause. That requires not episodic shows of force (such as the 2008-09 war against Hamas in Gaza) but a sustained and systematic effort to deflate a bellicose mentality.

Israel’s victory also directly helps its U.S. ally, for some of its enemies — Hamas, Hezbollah, Syria, and Iran — are also America’s. Tougher Israeli tactics would help Washington in smaller ways, too. Washington should encourage Jerusalem not to engage in prisoner exchanges with terrorist groups, not to allow Hezbollah to re-arm in southern Lebanon or Fatah or Hamas in Gaza, and not to withdraw unilaterally from the West Bank (which would effectively turn over the region to Hamas terrorists and threaten Hashemite rule in Jordan).

Diplomacy aiming to shut down the Arab-Israeli conflict is premature until Palestinians give up their anti-Zionism. When that happy moment arrives, negotiations can re-open and take up anew the Oslo issues — borders, resources, armaments, sanctities, residential rights. But that is years or decades away. In the meantime, an ally needs to win.

Daniel Pipes is publisher of the Middle East Quarterly and Taube distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution of Stanford University.