Bucking the Federal Reserve’s efforts to push interest rates lower, investors are selling off U.S. government debt, driving rates in many cases to their highest levels in more than three months.

The Fed’s $600 billion program to buy Treasury bonds began late last week and is kicking into high gear this week, with the central bank buying up tens of billions of dollars of debt.

That should have driven prices up on those bonds and lowered their interest rates, or yields, which move opposite to the price. Instead, yields on almost every Treasury have been rising.

The trend is a potential problem for the economy and the Fed. Rates had fallen sharply for months in anticipation of a Fed buying program, and in a short time much of that effect has been lost, spelling an unwelcome rise in borrowing costs throughout the economy.

That could throw a wrench in what the Fed is trying to accomplish: to use low rates to encourage more borrowing and risk-taking by consumers, businesses and investors, thereby reviving growth.

Still, it is far too early to declare that the Fed’s plan is failing, and many rates remain near historic lows.

And recent economic indicators, such as a Monday report on retail sales, suggest the economy continues to recover—which is the Fed’s ultimate concern.

“The recent run-up in bond yields is worrying to many,” said Dan Greenhaus, chief economic strategist at Miller Tabak, a New York trading firm, but “you need to keep it in context of what happened before the Fed moved.”

The Fed has only begun to put its plan in motion, and many investors are simply cashing out of lucrative bond-market bets they placed in the long prelude to the Fed’s announcement of its purchasing program.

Rates in most cases are still far lower than they were in the spring.

Many observers still believe that the power of the Fed’s printing press will prove overwhelming and economic growth disappointing. Both forces would eventually drive rates lower.

Still, the recent move in rates has been jarring, raising some market worries that the Fed’s program might be ineffective or backfiring. That could damage the Fed’s credibility and raise borrowing costs broadly

The recent move in interest rates may be due partly to the rosier tone of economic data recently, including data released on Monday that showed retail sales at their highest level since August 2008, the month before the fall of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. Sales rose 1.2% to $373.1 billion in October, compared with the month before.

If the economy keeps improving, then the Fed’s bond-buying program could end sooner than expected. That would be a much happier outcome for the Fed, though most economists still don’t expect it.

In an interview conducted last week, the Fed’s new vice chair, Janet Yellen, defended the program, given an economic outlook that seemed to portend high unemployment, low inflation and lackluster growth for some time.

“I’m having a hard time seeing where really robust growth can come from,” Ms. Yellen told The Wall Street Journal. “And I see inflation lingering around current levels for a long time.”

For now, the market seems to be driven mainly by the momentum of investors selling Treasury bonds to take a hefty profit after a rally that began in the spring, gathered steam as the economy weakened this summer and peaked amid talk of a new Fed buying program.

The 10-year Treasury note’s yield, which influences most residential mortgage rates, surged on Monday to 2.911%, the highest since Aug. 5. Bond prices and yields move in the opposite direction.

The 10-year note has now more than erased all of the beneficial effects of comments in late-August by Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke in Jackson Hole, Wyo., in which he first hinted at another round of bond-buying.

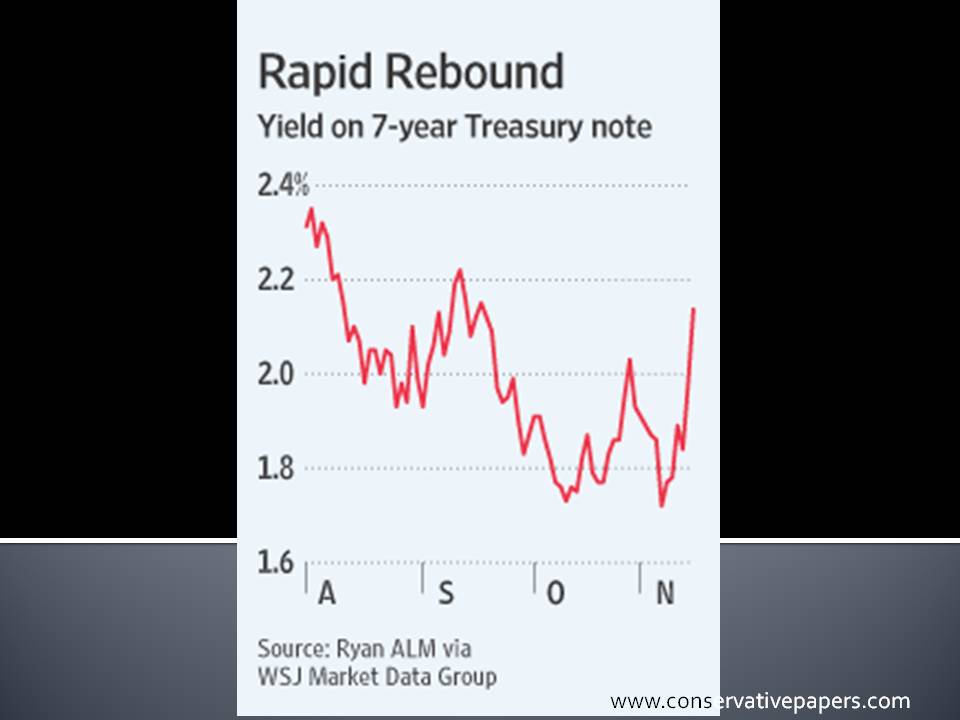

And on Monday, the yield on the 7-year Treasury note rose to 2.14%, a 2-month high, despite the Fed’s buying $7.92 billion in 6- and 7-year Treasury debt in the morning.

Yields were more or less steady while the Fed was buying, but surged through the end of the day.

Several other factors have been working against Treasurys in recent days, including a backlash against the Fed’s program overseas and among conservative politicians and economists in the U.S.

Corporate bond issuance has been heavy since the Fed announced its bond-buying plan, which often leads to a temporary selloff in Treasurys.

Moody’s Investors Service may have contributed to the punishment late on Monday when it warned that an extension of Bush-era tax cuts, set to expire on Dec. 31, could harm the country’s fiscal standing.

Though the tax-cut issue isn’t new, and though Moody’s said the U.S. credit rating was secure, the bond market is sometimes sensitive to rating-agency comments.

The Fed plans to buy Treasurys every day this week, including 2- to 3-year notes on Tuesday and 8- to 10-year notes on Wednesday. It has committed to buying through the second quarter of 2011.

It also plans to use whatever cash it gets from expiring mortgages on its balance sheet to buy still more Treasurys, taking total purchases closer to $900 billion, according to some estimates.

That, Mr. Greenhaus notes, is more Treasury debt than China owned at the end of August. “Those screaming the end of the bond-market rally might be better served by waiting just a bit longer,” he said.