Here are two problems with the U.S. economy that reinforce each other: Employers aren’t creating enough jobs, and big companies increasingly seek tax advantages by relocating overseas. A new study suggests there may be one solution to both problems: Cut the corporate tax rate by a sizable margin.

Republicans and Democrats agree in principle on the need to lower corporate tax rates and simplify the tax code. Now, a new study by S&P Capital IQ suggests such a move could carry the collateral benefit of creating 10 million jobs or more. This comes amid the growing popularity of corporate “tax inversions,” in which a U.S. company buys or merges with a foreign firm in order to relocate its headquarters to a country with lower tax rates. Medtronic (MDT) recently announced plans to buy Ireland’s Covidien (COV) and move its headquarters there, for instance, and Pfizer (PFE) would have made a similar deal with the UK’s AstraZeneca (AZN) except British regulators signaled disapproval.

With more big firms considering such a move and Congress beginning to hold hearings on the matter, S&P analyzed what would happen if Congress passed a law dropping the corporate tax rate by 10 percentage points. The answer: Government tax revenues would fall, but employers would create 10 million jobs or more, enough to offset the loss to the U.S. Treasury. “This would be a game-changer,” says Michael Thompson of S&P, who oversaw the research. “If the United States were one of the most competitive tax domiciles in the developed world, how would that change the math in a CEO’s or a CFO’s head? It would change it a lot.”

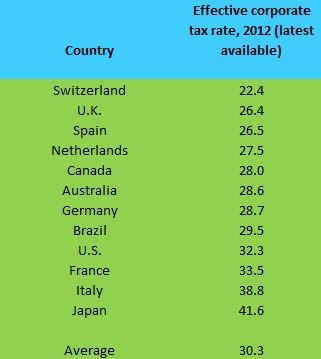

The official corporate tax rate in the United States is 35%, which is higher than in most other countries. But S&P calculated the “effective” corporate tax rate in several countries, which is what companies really pay after adding on state and local taxes and subtracting deductions and writeoffs. By that measure, corporate tax rates in the U.S. are moderate, as this table shows:

Still, that doesn’t stop U.S. multinationals from taking advantage of lower tax rates in other countries, especially when it comes to money earned overseas, which must be taxed at U.S. rates if repatriated. Overseas revenue earned by U.S. companies has been growing and now totals about 48% of all revenue earned by companies represented in the S&P 500 index. So the incentive for CEOs to move their companies out of the United States is getting stronger.

S&P analyzed what would happen if the effective U.S. corporate rate were dropped from 32.3% to 22.4%, which is what companies based in Switzerland pay. Overall, the U.S. government would lose about $91 billion in annual revenue, based on 2013 tax figures. That might sound like a big number, but it’s only about 3% of the $3 trillion or so Washington rakes in every year in tax revenue. That’s because corporate taxes only account for about 10% of federal revenue. Payroll and individual income taxes account for about 80%, with the rest coming from various types of fees and excise taxes.

S&P estimates it would take about 10 million additional jobs to generate enough tax revenue to make up for the smaller amounts corporations would pay. That, too, may sound like a stretch, in an economy that’s generating only about 200,000 new jobs per month. But S&P says that could actually happen: “The approximate 10 million-job target should be achievable and may even be conservative.”

Those jobs, in theory, would materialize as corporations built new facilities at home instead of setting up shop in foreign countries, and as they “reshored” facilities that are already overseas. Boston Consulting Group and others say this is already beginning to happen, as foreign labor costs rise and become less of a bargain, and a U.S. oil and gas boom promises cheaper energy than many firms can find overseas. The workers certainly ought to be available. “We’ve got 15 million people who should be working that aren’t working,” Thompson says. “We could easily put 10 million of those people back into the labor force.”

Many economists agree that lower corporate tax rates would stimulate growth to some extent, since U.S. companies by definition would have more money to spend in the United States. The problem with projections such as S&P’s is that it’s politically perilous to cut taxes on profitable corporations, on the premise that more middle-class jobs will materialize at some point in the future. Americans have been losing — not gaining — trust in big institutions, and they’re rightfully wary of anything that connotes corporate welfare.

Politicians have been all talk and no action on corporate tax reform, even though this is one political issue on which disagreements seem remediable. President Obama supports lowering the official corporate tax rate to 28%, while closing loopholes and raising taxes on rich individuals. Republicans want a lower corporate rate than 28%, while opposing higher taxes for anybody. Compromise, needless to say, has been elusive, though positions may soften as more companies split town.

By Rick Newman’s latest book is Rebounders: How Winners Pivot From Setback To Success. Follow him on Twitter: @rickjnewman.