Five years ago, Professor Miroslav Djordjevic, the world-leading genital reconstructive surgeon, received a patient at his Belgrade clinic. It was a transgender patient who had surgery at a different clinic to remove male genitalia – and had since changed their mind.

That was the first time Professor Djordjevic had ever been contacted to perform a so-called “reversal” surgery. Over the next six months, another six people also approached him, similarly wanting to reverse their procedures. They came from countries all over the Western world, Britain included, united by an acute sense of regret. At present, Professor Djordjevic has a further six prospective people in discussions with his clinic about reversals and two currently undergoing the process itself; reattaching the male genitalia is a complex procedure and takes several operations over the course of a year to fully complete, at a cost of some $18,000.

Those wishing the reversal, Professor Djordjevic says, have spoken to him about crippling levels of depression following their transition and in some cases even contemplated suicide. “It can be a real disaster to hear these stories,” says the 52-year-old. And yet, in the main part, they are not being heard.

Last week, it was alleged that Bath Spa University has turned down an application for research on gender reassignment reversal because it was a subject deemed “potentially politically incorrect”. James Caspian, a psychotherapist who specialises in working with transgender people, suggested the research after a conversation with Professor Djordjevic in 2014 at a London restaurant where the Serbian told him about the number of reversals he was seeing, and the lack of academic rigour on the subject.

According to Mr Caspian, the university initially approved his proposal to research “detransitioning”. He then amassed some preliminary findings that suggested a growing number of young people – particularly young women – were transitioning their gender and then regretting it.

But after submitting the more detailed proposal to Bath Spa, he discovered he had been referred to the university ethics committee, which rejected it over fears of criticism that might be directed towards the university. Not least on social media from the powerful transgender lobby.

Speaking this week, Mr Caspian described himself as “astonished” at the decision, while Bath Spa University has launched an internal inquiry into why the research was turned down and is at present refusing to comment further.

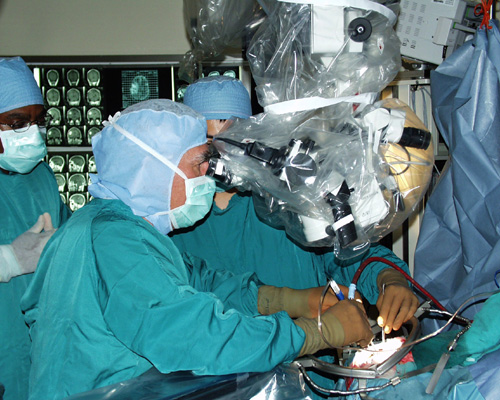

Until the investigation is complete, Professor Djordjevic, who performs around 100 surgeries a year both at his Belgrade clinic and New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital, is unwilling to give his exact opinion on the apparent rejection, but admits he is baffled as there is a desperate need for greater understanding in reversals.

“Definitely reversal surgery and regret in transgender persons is one of the very hot topics,” he says. “Generally, we have to support all research in this field.”

Professor Djordjevic, who has 22 years’ experience of genital reconstructive surgery, operates under strict guidelines. Before any surgery, patients must undergo psychiatric evaluation for a minimum of between one and two years, followed by a hormonal evaluation and therapy. He also requests two professional letters of recommendation for each person and attempts to remain in contact for as long as possible following the surgery. Currently, he still speaks with 80 per cent of his former patients.

Following conversations with those upon whom he has helped perform reversals, Professor Djordjevic says he has real concerns about the level of psychiatric evaluation and counselling that people receive elsewhere before gender reassignment first takes place.

Prof Djordjevic fears money is at the root of the problem, and says his reversal patients have told him about making initial inquiries to surgeries and simply being asked to send a cheque in return.

“I have heard stories of people visiting surgeries who only checked if they had the money to pay,” he says. “We have to stop this. As a community, we have to make very strong rules: nobody who wants to make this type of surgery or just make money can be allowed to do so.”

To date, all of his reversals have been transgender women aged over 30 wanting to restore their male genitalia. Over the last two decades, the average age of his patients has more than halved, from 45 to 21. While the World Professional Association for Transgender Health guidelines currently state nobody under the age of 18 should undergo surgery, Prof Djordjevic fears this age limit could soon be reduced to include minors. Were that to happen, he says, he would refuse to abide by the rules. “I’m afraid what will happen five to 10 years later with this person,” he says. “It is more than about surgery; it’s an issue of human rights. I could not accept them as a patient as I’d be afraid what would happen to their mind.”

Referrals to adult and child gender identity clinics in the UK have increased dramatically over the past 10 years. In April, the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, the only clinic for adolescents in England, reported 2,016 referrals to its gender identity development service, a 42 per cent rise compared to the previous year, which in itself marked a 104 per cent increase on the year before that.

The clinic stresses the majority of its young referrals do not end up receiving physical treatment through the service. While NHS guidelines state young people should not be given cross-sex hormone treatment until 16, concerns have been raised about the lack of regulation, particularly in the private sector.

Earlier this month, it was revealed a Monmouthshire MP, Dr Helen Webberley, was being investigated by the General Medical Council (GMC), following complaints from two GPs that she had treated children as young as 12 with hormones at her private clinic, which specialises in gender issues.

Dr Webberley insists she has done nothing wrong, and there were no “decisions or judgments” made on the claims against her. “There are many children under 16 who are desperate to start what they would consider their natural puberty earlier than that,” she said this month.

Professor Djordjevic feels differently, and admits he has deep reservations about treating children with hormonal drugs before they reach puberty – not least as by blocking certain hormones before they have sufficiently developed means they may find it difficult to undergo reassignment surgery in the future.

“Ethically, we have to help any person over the world starting from three to four years of age, but in the best possible way,” he says. “If you change general health with any drug, I’m not a supporter of that theory.”

These are profoundly life-changing matters around which he – like many in his industry – feels far better debate is required to promote new understanding. But at the moment, it seems, that debate is simply being shut down.