“If you apply for a job, they seem to give the blacks the first crack at it,” said 68-year-old Tim Hershman of Akron, Ohio, “and, basically, you know, if you want any help from the government, if you’re white, you don’t get it. If you’re black, you get it.”

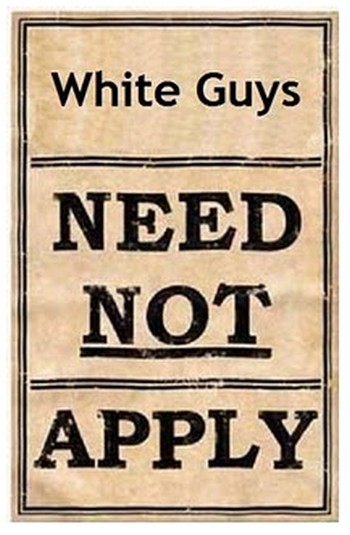

More than half of whites — 55 percent — surveyed say that, generally speaking, they believe there is discrimination against white people in America today. Hershman’s view is similar to what was heard on the campaign trail at Trump rally after Trump rally. Donald Trump catered to white grievance during the 2016 presidential campaign and has done so as president as well.

People from every racial or ethnic group surveyed said they believe theirs faces discrimination — from African-Americans and Latinos to Native Americans and Asian-Americans, as well as whites.

The responses from whites can be broken down into three categories. Those who:

1. Believe there is anti-white discrimination and say they have personally experienced it,

2. Say there is indeed anti-white discrimination but say they have never felt it themselves, and

3. Say there is no discrimination of whites in America

White and discriminated against?

Ask Hershman whether there is discrimination against whites, and he answered even before this reporter could finish the question — with an emphatic “Absolutely.”

“It’s been going on for decades, and it’s been getting worse for whites,” Hershman contended. Data shows Asians continue to be better off financially and educationally than all groups.

Even though Hershman believes he has been a victim of anti-white discrimination. He describes losing out on a promotion — and a younger African-American being selected as one of the finalists for the job due to affirmative action.

Discrimination exists, but never felt it

Representing Category 2 is 50-year-old heavy equipment operator Tim Musick, who lives in Maryland, just outside Washington, D.C. He says anti-white discrimination is real, but he doesn’t think he has ever really felt it personally.

“I think that you pretty much, because you’re white, you’re automatically thrown into that group as being a bigot and a racist and that somehow you perceive yourself as being more superior to everybody else, which is ridiculous,” Musick said, speaking during his lunch break at a construction site.

“I’m just a man that happens to have been born white,” Musick continued.

He also makes it clear, however, that he is not comparing what happens to whites to the African-American experience.

“I don’t know what it feels like to be a black man walking around in the streets, but I do know what it feels like to be pegged, because of how you look, and what people perceive just on sight,” said Musick, who has the stocky build of a retired NFL lineman and a shaved head under his hard hat.

Whites who don’t believe they are discriminated against

Now for the third category — those who scoff at the notion that whites face racial discrimination.

That describes retired community college English teacher Betty Holton, of Elkton, Md.

“I don’t see how we can be discriminated against when, when we have all the power,” Holton said, chuckling in disbelief into her cellphone.

“Look at Congress. Look at the Senate. Look at government on every level. Look at the leadership in corporations. Look. Look anywhere.”

Holton asserts: “The notion that whites are discriminated against just seems incredible to me.”

Perception based on income

Income also seemed to affect individual responses to the question of discrimination.

Lower- and moderate-income white Americans were more likely to say that whites are discriminated against — and to say they have felt it, either when applying for a job, raise or promotion or in the college-admissions process.

“We’ve long seen a partisan divide with Democrats more likely to say racial discrimination is that reason blacks can’t get ahead, but that partisan divide is even bigger than it has been in the past,” said Jocelyn Kiley, an associate director at Pew Research Center. “That’s a point where we do see that partisan divides over issues of race have really increased in recent years.”

What this could mean for electoral politics

David Cohen, a political scientist at the University of Akron, said the finding that a majority of whites say whites are victims of discrimination fits right into one of the big narratives of the last presidential campaign.

“I think this does reinforce a lot of the resentment you saw in the 2016 election, especially among white, working-class voters lacking a college degree,” said Cohen, who lives in northeastern Ohio, a traditionally Democratic stronghold full of white, working-class union members.

Trump ran far better there, though, than Republicans typically do, as he easily won the battleground state of Ohio, 52 percent to 44 percent.

But Cohen also adds that for all of the talk of Trump’s message speaking directly to whites in the working class — white voters overall supported him in about the same numbers as they did for Mitt Romney four years earlier — 58 percent for Trump, 59 percent for Romney.

And though it’s possible that Trump’s message to disaffected whites did make a difference in the decisive battleground states of Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, Cohen said the question remains: Did Trump create or significantly boost white resentment overall — or did he simply tap into a trend with deep roots and history?

“I’m not sure that he necessarily created this angst among white voters,” Cohen said, “but he certainly knew how to take advantage of it.”

And it’s something Trump — as president — has only continued to tap into.