Engineering of the Colorado River may have delayed an overdue large earthquake along the southern San Andreas Fault, UC San Diego researchers say in a new study.

But as stresses keep building, faults under the Salton Sea may trigger a big quake anyway, the researchers said.

The faults, some of which the researchers discovered, could trigger ruptures in a “strike-slip stepover zone,” they said. That’s the same fault configuration that triggered the disastrous 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

Strike-slip faults are vertical or nearly vertical, caused when adjacent land blocks, or plates, move horizontally.

They are a common cause of earthquakes in California, said Neal Driscoll, a study author and professor at UCSD’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

A stepover zone is an area where faults are close enough that movement on one can trigger another.

“Such an event could propagate northward, producing strong shaking and significant damage to the Los Angeles metropolitan area,” said the study, published online Sunday in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Simulations of northward-trending earthquakes along the San Andreas Fault indicate that they will be more damaging than any going south, the paper said.

“We’ve learned if we start the fault propagating from south to north, large metropolitan areas like Riverside and Los Angeles will experience more ground shaking than if it propagates from north to south,” said Driscoll.

He said the discovery that the direction an earthquake travels can affect its intensity is a major research finding.

The researchers performed a sonar scan of the sediment underneath the Salton Sea, unexpectedly discovering so-called “normal faults,” Driscoll said.

Normal faults occur when the plates are being pulled in opposite directions, causing one side to drop.

Lake Elsinore will get a similar scan this summer to determine its fault structure, he said.

Big earthquakes have occurred under the Salton Sea about once every 180 years over the past 1,000 years, the researchers said.

They studied sediments and discovered that earthquakes occurred repeatedly whenever the Colorado River rapidly flooded the lake basin.

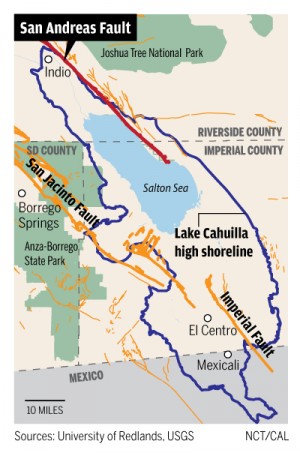

The river periodically changed course, either emptying south into the Gulf of Mexico or north into what became an ancient lake, much larger than the Salton Sea, called Lake Cahuilla.

However, there hasn’t been a big earthquake under the Salton Sea for 300 years, which is how long it has been since the last big flood, the study said. (The man-caused mistake that created the Salton Sea in 1905-1907 was small by comparison, so it’s not likely to trigger a big earthquake.)

The timing correlation doesn’t mean that cause and effect are proven, said Debi Kilb, a study author and seismologist at UCSD’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

However, various computer models of fault stress agree that the rapid flooding is sufficient to trigger earthquakes.

The floods periodically created Lake Cahuilla, six times the size of the present-day Salton Sea.

Lake Cahuilla’s surface reached 85 meters, or 279 feet, above that of the present-day Salton Sea.

The weight of that water pressed down on the faults underneath, nudging them to move.

“Now with regulation of the Colorado River for agriculture and municipalities, we’ve prevented these flooding events,” Driscoll said.

However, the stress keeps increasing, as Earth’s tectonic plates keep moving. The Pacific plate, bounded on the east by faults such as the San Andreas Fault, is moving northwest against the North American plate about 50 millimeters per year, Driscoll said.

“A lot of people get this idea that it (the plate boundary) is this line, and it’s not,” Driscoll said. “It’s a series of faults with the San Andreas being the easternmost, San Jacinto, Elsinore, Rose Canyon, Newport. It’s a big zone that accommodates this deformation. The San Andreas and San Jacinto accommodate the majority of it.

“So we’re building up what we call tectonic stress. And as this tectonic stress builds up, you can imagine if there’s a lot of stress across the fault and I load it with the lake, that might trigger it,” he said. “So now, because we’re not loading it with flooding, one might postulate that there’s going to be a longer time of buildup, because we’ll have to get to the tectonic stress threshold.”

As for how long that might take?

“We don’t know,” Driscoll said. “Meet me here in 2,000 years and I’ll tell you.”

Others who took part in the study are Karen Luttrell of Scripps Institution of Oceanography; Daniel Brothers of Woods Hole Coastal and Marine Science Center in Woods Hole, Mass; and Graham Kent of Nevada Seismological Laboratory at University of Nevada, Reno.