by Daniel Pipes

National Review Online

September 27, 2011

In a Middle East wracked by coups d’état and civil insurrections, the Republic of Turkey credibly offers itself as a model thanks to its impressive economic growth, democratic system, political control of the military, and secular order.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan effectively bought the June 2011 elections by pumping credit into the Turkish economy.

But, in reality, Turkey may be, along with Iran, the most dangerous state of the region. Count the reasons:

Islamists without brakes: When four out of five of the Turkish chiefs of staff abruptly resigned on July 29, 2011, they signaled the effective end of the republic founded in 1923 by Kemal Atatürk. A second republic headed by Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdo?an and his Islamist colleagues of the AK Party began that day. The military safely under their control, AKP ideologues can now pursue their ambitions to create an Islamic order.

An even worse opposition: Ironically, secular Turks tend to be more anti-Western than the AKP. The two other parties in parliament, the CHP and MHP, condemn the AKP’s more enlightened policies, such as its approach to Syria and i ts stationing a NATO radar system.

Looming economic collapse: Turkey faces a credit crunch, one largely ignored in light of crises in Greece and elsewhere. As analyst David Goldman points out, Erdo?an and the AKP took the country on a financial binge: bank credit ballooned while the current account deficit soared, reaching unsustainable levels. The party’s patronage machine borrowed massive amounts of short-term debt to finance a consumption bubble that effectively bought it the June 2011 elections. Goldman calls Erdo?an a “Third World strongman” and compares Turkey today with Mexico in 1994 or Argentina in 2000, “where a brief boom financed by short-term foreign capital flows led to currency devaluation and a deep economic slump.”

Sending the Mavi Marmara to Gaza amounted to an intentional provocation.

Escalating Kurdish problems: Some 15-20 percent of Turkey’s citizens identify as Kurds, a distinct historical people; although many Kurds are integrated, a separatist revolt against Ankara that began in 1984 has recently reached a new crescendo with a more assertive political leadership and more aggressive guerrilla attacks.

Looking for a fight with Israel: In the tradition of Gamal Abdel Nasser and Saddam Hussein, the Turkish prime minister deploys anti-Zionist rhetoric to make himself an Arab political star. One shudders to think where, thrilled by this adulation, he may end up. After Ankara backed a protest ship to Gaza in May 2010, the Mavi Marmara, whose aggression led Israeli forces to kill eight Turkish citizens plus an ethnic Turk, it has relentlessly exploited this incident to stoke domestic fury against the Jewish state. Erdo?an has called the deaths a casus belli, speaks of a war with Israel “if necessary,” and plans to send another ship to Gaza, this time with a Turkish military escort.

Stimulating an anti-Turkish faction: Turkish hostility has renewed Israel’s historically warm relations with the Kurds and turned around its cool relations with Greece, Cyprus, and even Armenia. Beyond cooperation locally, this grouping will make life difficult for the Turks in Washington.

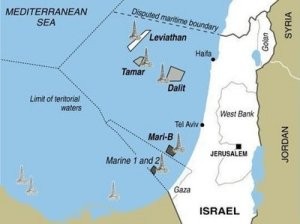

Asserting rights over Mediterranean energy reserves: Companies operating out of Israel discovered potentially immense gas and oil reserves in the Leviathan and other fields located between Israel, Lebanon, and Cyprus. When the government of Cyprus announced its plans to drill, Erdo?an responded with threats to send Turkish “frigates, gunboats and … air force.” This dispute, just in its infancy, contains the potential elements of a huge crisis. Already, Moscow has sent submarines in solidarity with Cyprus.

The Leviathan gas field is the largest of several found recently between Cyprus and Israel.

Other international problems: Ankara threatens to freeze relations with the European Union in July 2012, when Cyprus assumes the rotating presidency. Turkish forces have seized a Syrian arms ship. Turkish threats to invade northern Iraq have worsened relations with Baghdad. Turkish and Iranian regimes may share an Islamist outlook and an anti-Kurd agenda, with prospering trade relations, but their historic rivalry, contrary governing styles, and competing ambitions have soured relations.

While Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu crows that Turkey is “”right at the center of everything,” AKP bellicosity has soured his vaunted “zero-problems” with neighbors policy, turning this into a wide-ranging hostility and even potential military confrontations (with Syria, Cyprus, and Israel). As economic troubles hit, a once-exemplary member of NATO may go further off track; watch for signs of Erdogan emulating his Venezuelan friend, Hugo Chávez.

That’s why, along with Iranian nuclear weapons, I see a rogue Turkey as the region’s greatest threat.

Mr. Pipes (www.DanielPipes.org) is president of the Middle East Forum and Taube distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution of Stanford University. © 2011 by Daniel Pipes. All rights reserved.

Sep. 27, 2011 update: For a miniature example of AKP bellicosity, note the fracas at the United Nations in recent days as the prime minister and foreign minister bounded about the place with their bodyguards, making trouble.

Source material can be found at this site.