Doubts are growing about whether China can pass the US to become the world’s biggest economy this century amid warnings that the country’s 30-year miracle is nearing exhaustion.

The world’s tallest tower should have been built by now. Officials said last year that the great edifice with 220 floors would be erected in three months flat in China’s inland city of Changsha by March, snatching the crown from Dubai’s Burj Khalifa.

The deadline has come and gone, yet the wasteland sits untouched. It now looks as if the fin d’époque project – using prefab blocs – may never be approved. Even China knows its limits.

Prime minister Li Keqiang has asked the State Council to clamp down on the excesses of the regions. Not before time. A top regulator says local government finances are “out of control”.

Mr Li aims to cut China’s economic growth to a safe speed limit of 7pc next year and rein in rampant investment – still a world record 49pc of GDP – before it traps the country in a boom-bust dynamic of frightening scale.

Vested interests are conspiring to stop him, launching a counter-attack from their power-base in the $6 trillion state industries. Even so, uber-growth is surely over.

China’s catch-up spurt has a few more years to run in the Western hinterlands perhaps, but when the full story comes out we may find that nationwide growth has already fallen below 7pc.

Mr Li complained in a US diplomatic cable released on WikiLeaks that Chinese GDP statistics are “man-made”, confiding to a US diplomat that he tracked electricity use, rail cargo, and bank loans to gauge growth. For a while, analysts use electricity data as a proxy for GDP but the commissars kept a step ahead by ordering power utilities to fiddle the figures.

The National Bureau of Statistics has since revealed that data collected by the regions overstates GDP by 10pc, though they have not acted on the insight. It is well-known why this goes on. The reward system of the Communist hierarchy has been geared to talking up growth, and officials gain kudos by lowering the stated “energy intensity” of their zone.

China’s Development Research Council (DRC) expects growth to drop to 6pc by 2020. It could be much lower. The US Conference Board says it will average 3.7pc from 2019-2025 as the ageing crisis hits. Michael Pettis from Beijing University thinks it is likely to slow to 3pc to 4pc over the next decade, deeming this entirely desirable if it comes from taming the runaway state enterprises.

If so, China’s growth may not be much higher than the new consensus estimate of 3pc for a reborn America, powered by its energy boom and the revival of the chemical, steel, glass, and paper industries.

All those charts showing China’s economy surging past the US by 2030, or 2025, or even 2017, will look very credulous. China may not surpass the US this century.

As of last year US GDP was roughly $15.7 trillion, compared to $8 trillion for China on a nominal exchange rate basis, the measure that matters for gauging economic power.

China’s output is 75pc of US levels on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis but even on this measure the Chinese `sorpasso’ is looking less certain. Clyde Prestowitz, an arch US `declinist’ who has just thrown in the towel, says China may “never” catch the US on any relevant measure. That is a stretch, but not impossible on a forecastable horizon.

“Keep in mind the next time you are in China and find yourself choking on the foul air that the things making the air foul are counted as positives for GDP. If you adjust Chinese GDP for environmental degradation and for over-investment in things that will never be used, it falls in size by 30-50 per cent. Much of this would show up as non-performing loans in most economies but since such loans are never recognised in China, it will show up as slower growth in future years,” he said.

A new view is taking hold in elite circles that the banking crash in 2008 was a nasty shock for the US, but not a crippling blow to America’s creative enterprise. US governing institutions rose to the challenge. It was however a crippling blow to Europe, and a more subtle blow to China in all kinds of ways.

Richard Haass, president of the US Council of Foreign Relations, says the world may already be in the “second decade of another American century” without realising it.

On almost every key measure, including the fertility rate and high science, there is no credible challenger. Core US defence spending is still greater than that of the next 10 countries combined. “The American qualitative military edge will be around for a long, long time,” he said.

Mr Haass says America has managed its dominance in such a way that it has not brought about a containment alliance against it by threatened powers, and that is no small achievement. Like Wagner’s music, US diplomacy is better than it seems.

Yes, the US faces a debt hangover, but so does China after the state banks let rip with private loans keep the boom going through the downturn. Fitch Ratings has just downgraded China’s debt, warning that credit has jumped from 125pc to 200pc of GDP over the last four years, with mounting reliance on shadow banking that lets banks circumvent loan-to-deposit curbs. This is why George Soros has been warning that there could be a “run” on China’s state banking system akin to the Lehman bust.

Total credit has jumped from $9 trillion to $23 trillion in four years, an increase equal to the entire US banking system.

America has moved in the opposite direction. Its banks now have loan-to-deposit ratio of around 0.7, and the biggest safety buffers in three decades. The Congressional Budget Office says US Treasury debt held by the public has jumped from 40pc to 73pc. This is the sort of damage normally seen in wars, but the US has recovered from bigger wars before, and from much higher debt levels. The CBO thinks the budget deficit will fall to 2.4pc by 2015. Growth will then whittle away the debt ratio for a few years.

China’s premier Li is fighting a battle against those in the Politburo who delude themselves that the Lehman crisis validates China’s top down control. He gave his “unwavering report” last year to a joint DRC and World Bank report on the dangers of the “middle income trap”.

Dozens of states in Latin America, Asia, and the Middle East have hit an invisible ceiling over the last fifty years, languishing in the trap with per capita incomes far behind the rare “breakout” stars, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. The trap is the norm.

The report warned that China’s 30-year miracle is nearing exhaustion. The low-hanging fruit of state-driven industrialisation and reliance on cheap exports has already been picked. Stagnation looms unless Beijing embraces the free market and relaxes its suffocating grip over the economy. “Innovation at the technology frontier is quite different in nature from catching up technologically. It is not something that can be achieved through government planning,” it said.

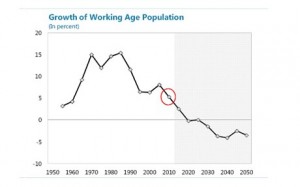

Even if Mr Li succeeds in pulling off this second economic revolution – and we should salute him for trying – China’s growth rate is going to slow drastically. Demography will see to that.

The work force began to contract in absolute numbers last year, falling by 3.5 million. The International Monetary Fund says it will now go into “precipitous” decline, and much earlier than thought.

If you are wondering why police are still seizing pregnant women in Chinese cities and delivering them to clinics for forced abortions when they cannot pay the fine for breaching the one-child policy, you are not alone.

The IMF says the reserve army of peasants looking for work peaked at around 150m in 2010. The surplus will evaporate soon after 2020, the so-called Lewis Point. A decade later China will face a shortage of almost 140m workers. “This will have far-reaching implications for both China and the rest of the world.”

China’s ageing crisis is tracking Japan’s tale with a 20-year delay. China can expect to see the same decline in “marginal productivity” that has afflicted every other facing a rise in the old-age dependency ratio.

The authorities can of course keep the game going if they wish with another burst of credit, but risks are rising and the potency of debt is wearing off. The extra output created by each yuan of lending has halved in four years. Mr Li knows the game is turning dangerous.

A 2010 book by People’s Army Colonel Liu Mingfu – “China Dream: Great Power Thinking and Strategic Posture in the Post-American Era” – is still selling like hot cakes in China. Yet it already has a dated feel, a throwback to peak hubris.

China has everything to play for. With skill and a blast of freedom, it can take its rightful place at the forefront of world affairs. But nothing is foreordained.